Planning for a child’s education is essentially a long‑horizon financial engineering task: you are matching future liabilities (tuition, housing, materials) with an investment strategy today. Instead of treating it as a vague goal, it helps to think in terms of cash‑flow modeling, risk management and tax optimization. This perspective makes it easier to compare approaches and understand which one aligns with your budget, risk tolerance and the specific milestones you want to fund.

Historical background of saving for education milestones

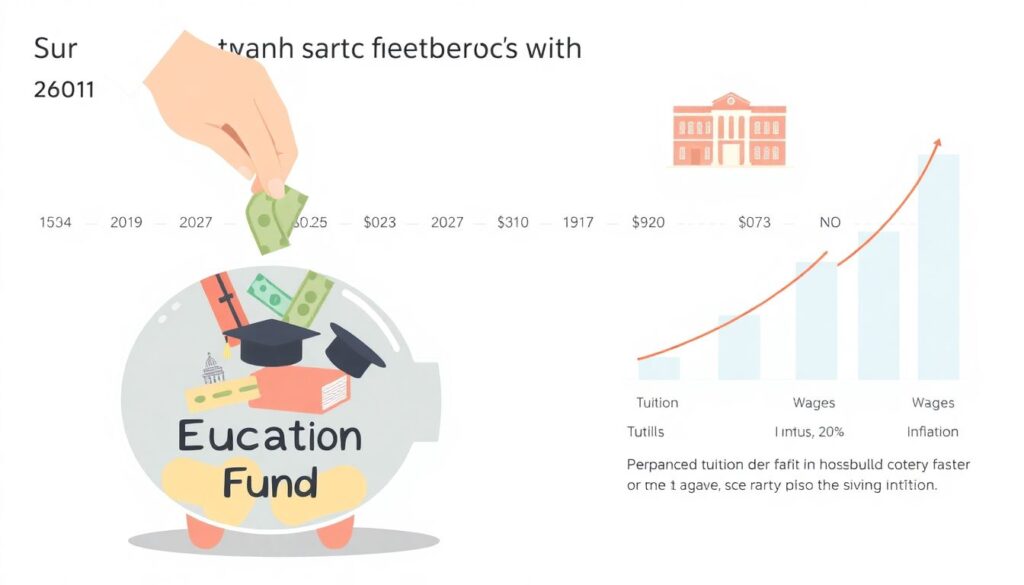

Systematic saving for children’s education emerged alongside the mass expansion of secondary and higher education in the 20th century. As tuition and associated costs started to grow faster than average wages and inflation, households could no longer rely on current income to fund university expenses. Initially, families mostly used simple savings accounts and government bonds. The real yield was often positive, so keeping money in low‑risk instruments still preserved purchasing power. Over time, however, inflation and rising tuition created a structural gap that required more sophisticated education investment plans for children, including equity exposure and tax‑advantaged vehicles.

In the United States, the turning point came with the creation of tax‑favored education accounts in the late 20th century. 529 plans, Coverdell Education Savings Accounts and various custodial accounts were introduced to incentivize early, disciplined saving. Other countries developed their own solutions: education endowment plans, government premium bonds for students, subsidized state loans and matched savings schemes. As financial markets globalized, parents began comparing products across borders, conducting their own informal 529 college savings plan comparison against local alternatives like junior ISAs in the UK or education endowments in parts of Asia, looking for the most efficient blend of return, risk and tax benefits.

Basic principles of education saving and investing

Regardless of country or instrument, several fundamental principles define a robust framework for funding education milestones. The first is time‑horizon analysis: the younger the child, the longer the compounding period and the more equity risk you can usually tolerate. This allows you to use diversified stock index funds early on and gradually shift toward bonds and cash as the enrollment date approaches. The second principle is liability matching: estimate target costs in future dollars, not today’s prices, by applying realistic tuition inflation assumptions rather than headline CPI. This converts a vague dream into a concrete funding target that can be monitored and adjusted annually.

Equally important is tax and fee efficiency. Many parents intuitively ask what the best savings plan for child education is without decomposing the answer into tax treatment, internal expenses, and flexibility. A tax‑advantaged wrapper with low‑cost index funds can dramatically improve risk‑adjusted returns versus a high‑fee “education” policy with opaque charges. In addition, you must integrate liquidity management: decide which milestones you are funding (preschool, private K‑12, undergraduate, graduate school) and in what order, then allocate assets so that short‑term liabilities are covered with low‑volatility instruments while long‑term goals remain in growth assets.

Key technical principles commonly used by planners include:

– Present value and future value calculations to estimate required monthly contributions.

– Strategic asset allocation based on risk capacity, not just risk tolerance.

– Scenario analysis to stress‑test tuition shocks, income interruption and market drawdowns.

– Tax‑loss harvesting and rebalancing to maintain the target risk level as markets move.

When people research how to start saving for child’s college, they often focus on the initial deposit amount, but a more rigorous approach is contribution design. Automating monthly transfers, integrating employer benefits where available, and periodically increasing contributions with income growth are often more powerful than trying to time the market or pick “star” funds. The process becomes a systematic savings algorithm rather than a sequence of ad‑hoc decisions driven by headlines or fear.

Comparing approaches and practical implementation examples

In practice, parents face several competing architectures for building an education portfolio. One common model is the tax‑advantaged education account, such as a 529 plan in the US. These vehicles allow after‑tax contributions, tax‑deferred growth and tax‑free withdrawals for qualified education expenses. A rigorous 529 college savings plan comparison typically examines state tax deductions, investment menu quality, underlying fund expenses and flexibility in changing beneficiaries. For families with stable income and clear college intentions, a 529 can serve as the core engine, with taxable brokerage accounts acting as a supplemental, more flexible layer.

An alternative architecture relies mainly on generic investment accounts or brokerage portfolios, using low‑cost ETFs and index funds without any education‑specific wrapper. This approach sacrifices dedicated tax perks but offers maximum flexibility: funds can be repurposed for non‑education goals without penalties. It can be particularly attractive in jurisdictions without strong education incentives or where future plans (e.g., studying abroad, entrepreneurship instead of college) are highly uncertain. Here, the emphasis is on broad asset allocation, diversification and monitoring child education savings account rates only when considering residual cash and short‑term instruments, rather than as the primary growth driver.

Typical implementation paths include:

– Core 529 or similar tax‑advantaged plan for projected tuition, plus a side taxable account for flexibility and “optional” costs such as study‑abroad or gap‑year funding.

– Pure investment portfolio in index funds when tax advantages are minimal or the child may choose nontraditional education paths.

– Insurance‑linked or endowment‑type policies in regions where they are tax‑efficient and heavily subsidized, surrounded by a more transparent investment portfolio to offset their rigidity.

To illustrate, consider two families with similar incomes but different risk preferences. Family A uses a 529 with an age‑based glidepath: high equity allocation in the early years, automatically shifting to bonds and cash as college nears. They contribute a fixed monthly amount indexed to wage growth. Family B prefers full control and starts with a global equity ETF portfolio in a taxable account, later adding municipal bonds as the child enters secondary school. Both can reach similar funding levels, but their tax outcomes and behavioral experience will differ, demonstrating that there is no single universal “best” architecture—only structures matched to constraints and preferences.

Examples of specific tools and step‑by‑step execution

From an operational standpoint, moving from theory to execution involves selecting concrete instruments and automating workflows. In the US context, many parents treat a 529 as the default best savings plan for child education, particularly when their state offers deductions or credits on contributions. The typical sequence is to choose a low‑cost, broad‑market age‑based portfolio within the 529, set up automatic monthly contributions aligned with cash‑flow capacity, and periodically review whether the target funding level is on track relative to projected tuition. In parallel, a high‑yield savings account or money market fund can serve as a buffer for near‑term education expenses such as tutoring or private school fees.

Outside the US, or for families seeking diversification, generic education investment plans for children can include a mix of mutual funds, ETFs, government bonds and, in some jurisdictions, tax‑incentivized insurance wrappers. Implementation then revolves around constructing a formal investment policy statement specifying asset classes, rebalancing rules, and contribution schedules. Rather than chasing headline child education savings account rates, the focus shifts to the portfolio’s expected real return net of fees and taxes, its volatility profile, and its correlation with other household assets like real estate or business equity.

A practical execution roadmap might look like this:

– Define the education milestones: private schooling, undergraduate, postgraduate, professional certifications.

– Quantify target costs in future values, including tuition inflation and living expenses.

– Select the primary savings vehicle (tax‑advantaged plan vs. taxable account vs. mixed model).

– Design a strategic asset allocation and document rebalancing thresholds.

– Automate contributions and set annual review dates to update assumptions and adjust.

For parents starting later, implementation may also incorporate more aggressive initial equity allocations combined with contingency plans: increased savings rates, potential use of student loans as a secondary funding layer, or partial coverage of costs instead of aiming for 100%. These choices illustrate how financial planning for education is a dynamic optimization process, not a static decision made once at birth.

Common misconceptions and analytical corrections

A widespread misconception is that safety equals keeping all education savings in cash or basic savings accounts. While capital preservation feels intuitive, over long horizons this strategy often results in a negative real return after inflation and tuition growth, effectively eroding purchasing power. Evaluated through a discounted cash‑flow lens, an all‑cash strategy for a newborn can be riskier in terms of funding shortfall than a diversified portfolio with measured equity exposure. Another myth is that starting small is pointless; in reality, even modest early contributions leverage the power of compounding, and later income growth can be used to scale savings rates as the milestone approaches.

Parents also frequently overestimate the rigidity of education‑specific accounts. Many modern structures allow beneficiary changes within the family or conversion of unused funds to support other educational paths. At the same time, some families believe that any product labeled as an “education plan” is automatically efficient, overlooking opaque fee structures and subpar underlying investments. A technical review of internal rate of return, fee drag and tax impact often reveals that some branded products underperform a plain, low‑cost index portfolio held in a tax‑efficient wrapper. This is why a disciplined 529 college savings plan comparison or equivalent analysis in your jurisdiction is crucial, rather than relying on marketing materials.

Persistent myths can be summarized as follows:

– “It’s too early, I’ll save when my income is higher” – ignores time diversification and compounding.

– “Cash accounts are the safest and therefore best” – neglects long‑term inflation and tuition risk.

– “Education‑branded policies are always better than generic investments” – disregards fees and flexibility.

– “If my child doesn’t go to college, all the money is wasted” – often untrue given modern rollover and beneficiary change rules.

Correcting these misconceptions requires reframing education saving as a structured, quantitative planning exercise instead of a one‑off product purchase. By integrating time horizon, tax optimization, investment risk and behavioral discipline into a single framework, parents can evaluate multiple approaches side by side and select the configuration that best fits their financial architecture and their child’s potential educational path.