Historical perspective on cash flow in tough times

From early crises to modern recessions

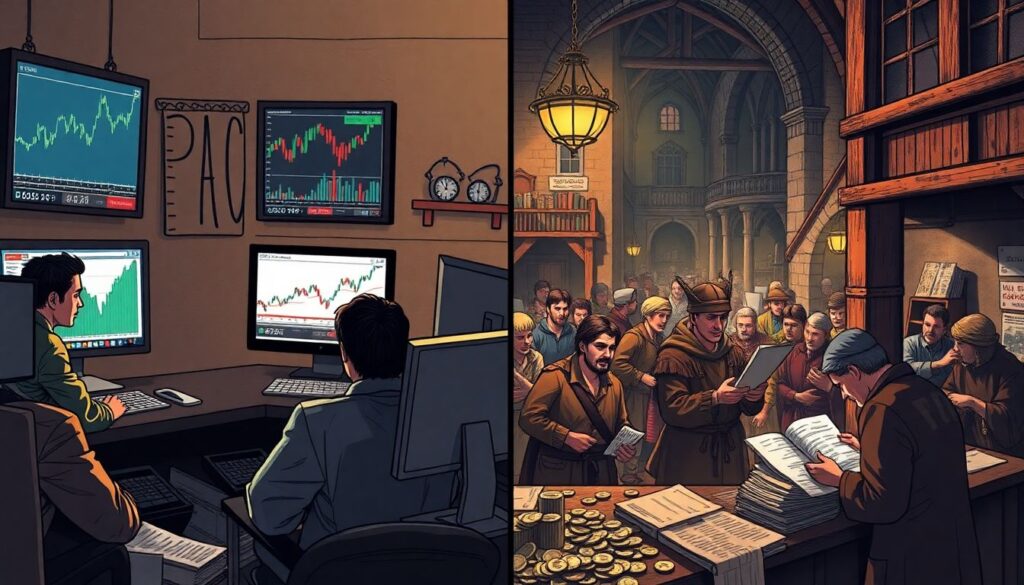

When people talk about downturns, they usually think of the dot-com crash or the 2008 crisis, but managing cash flow under pressure is as old as business itself. Merchants in medieval cities already knew that the one who survived bad harvests and trade disruptions was not the one with the highest profits, but the one with enough coins in the chest to pay suppliers and workers until demand recovered. That same logic still drives modern cash flow management strategies for small businesses, even if the tools have changed from ledgers and quills to cloud dashboards and mobile alerts.

Lessons from past downturns

If you look at the Great Depression, the oil shocks of the 1970s, the 2001 dot-com bust or the 2008 financial crisis, the same pattern shows up: sales fall, banks get cautious, and companies that rely on constant borrowing suddenly find the door half‑closed. The firms that made it through usually shared three habits: they tracked cash flows weekly (sometimes daily), cut non‑essential spending early rather than late, and negotiated longer payment terms before the situation became desperate. Modern business cash flow solutions for economic downturn may look more sophisticated, but the core discipline—protecting liquidity first, then worrying about growth—comes straight from those earlier crises.

—

Basic principles of managing cash flow during downturns

Principle 1: Cash is a constraint, not a detail

Accounting profit can be comforting, but during a recession you pay rent, payroll and suppliers with cash, not with “profit” on paper. That means the first principle of how to improve cash flow during a recession is to treat available cash like a hard ceiling for your decisions. Before committing to any project or hire, you ask not “Is this profitable on average?” but “What does this do to my bank balance over the next 3–6 months?” This shift in thinking pushes you to reconsider generous payment terms, slow‑moving stock and vanity projects that drain liquidity without protecting core revenue.

Principle 2: Shorten the time between outflow and inflow

In any business model, there is a time gap between when you spend money and when you get it back. In calm times, that gap hides in the background; in a downturn it can become lethal. A practical rule: try to shrink the gap on the revenue side and stretch it (ethically) on the cost side. That may mean invoicing faster, asking for deposits, moving to subscription models, or offering small discounts for early payment—while at the same time negotiating with landlords, vendors and lenders for more flexible schedules. The aim is to keep the cash conversion cycle as tight as possible so shocks hurt less.

Principle 3: Build a rolling cash forecast, not a static budget

Static annual budgets become outdated weeks into a serious downturn. That is why many experts insist that even the smallest firms maintain a short‑term, rolling cash forecast. Unlike a budget, which is about expectations, a forecast is about survival: it maps expected inflows and outflows over the coming 13 weeks and gets refreshed every week as new information arrives. For growing firms, partnering with external cash flow forecasting services for SMEs can make this process more rigorous, turning guesswork into a disciplined routine. The forecast becomes your early‑warning radar for problems that are still invisible on the income statement.

Principle 4: Use tools, but keep your hands on the wheel

Technology can dramatically strengthen your cash discipline. The best cash flow management software for small business can synchronize bank feeds, categorize payments, predict shortfalls and even simulate scenarios. But software is a tool, not a substitute for judgment. You still need to decide which customers are truly strategic, which expenses are optional, and what risks you are willing to carry. In other words, you use tools to see the numbers faster and more clearly, then apply human thinking—especially in a downturn, when emotions run high and panic can distort both optimistic and pessimistic decisions.

—

Examples of implementation in real businesses

Example 1: Service firm tightening its billing and payment habits

Imagine a small marketing agency that suddenly loses two big clients when the economy slows. On paper, the owner is profitable, but cash is getting tight because clients pay 60 days after receiving invoices while salaries and rent go out every month. Following expert advice, the owner first maps every recurring cash outflow and then looks at the inflows, week by week. She changes contracts so new clients pay 30% upfront, shortens payment terms from 60 to 30 days where possible, and introduces automatic reminders for overdue invoices. It is a classic case of very practical cash flow management strategies for small businesses: no exotic finance, just discipline around how cash enters and leaves the company.

Example 2: Manufacturer rethinking inventory and suppliers

Consider a small manufacturer supplying parts to larger industrial clients. When orders drop during a downturn, the warehouse is left full of slow‑moving stock, and cash is trapped on the shelves. Instead of cutting staff immediately, the management team works through their business cash flow solutions for economic downturn with outside consultants. They reduce product variants, standardize components to buy longer runs of fewer items, and renegotiate framework agreements with key suppliers, trading a slightly higher unit price for smaller, more frequent deliveries. This lowers inventory, frees up cash and still keeps the supply chain stable enough to respond if demand returns.

Example 3: Retailer going digital and diversifying revenue

A local retailer facing a sharp fall in foot traffic decides not to wait for things to “go back to normal.” Guided by financial and marketing experts, they move part of their assortment online, introduce click‑and‑collect, and set up subscription boxes for loyal customers. This combination speeds up cash inflows because subscribers pay in advance, while online channels reduce reliance on a single revenue stream. At the same time, the owner uses simple digital tools to track daily cash position, so the impact of each experiment is visible almost immediately. The story shows that managing cash flow is not only about cutting; it is also about redesigning how and when you get paid.

—

Practical expert recommendations for downturn cash flow

Five concrete steps advisors often recommend

1. Create a 13‑week cash forecast and update it weekly.

Experts repeatedly stress that this is the single most effective habit. Build a simple calendar of expected receipts and payments for the next three months. Every week, replace estimates with actuals and roll the forecast forward. You will spot shortfalls early enough to negotiate or adjust spending rather than scrambling at the last moment.

2. Segment customers by payment behavior, not just by revenue.

Many advisors suggest going beyond simple “big vs small” client lists. Identify who pays on time, who slips regularly and who drains your team with disputes. During a downturn, focus limited resources on collecting from reliable payers, and consider stricter terms or partial prepayments for chronic late‑payers, even if they look attractive in pure sales volume.

3. Freeze non‑essential spending for 30 days and then re‑allow selectively.

Instead of cutting randomly, experts propose a short, sharp pause on everything that is not clearly linked to revenue or critical operations. For one month, you hold back on travel, training, décor, nice‑to‑have software and side projects. After that, you reinstate only the items that show a clear contribution to cash flow or strategic value.

4. Talk to lenders and suppliers before you are desperate.

Seasoned turnaround consultants are adamant about timing: banks and key suppliers are more open to flexible terms and temporary arrangements when they see proactive, transparent management. Use your updated forecast to show them you understand the numbers and have a realistic plan. This increases your chances of getting extended terms, interest‑only periods or restructured schedules.

5. Build a “cash culture” inside the team.

CFOs with crisis experience often note that cash control fails when only the finance team cares about it. Explain to staff, in plain language, why prompt invoicing, careful purchasing and negotiating deposits matter for their jobs. Small actions—like project managers sending invoices the same day a milestone is reached—can cumulatively change your cash position far more than one big loan.

How technology and external support fit in

Financial experts frequently highlight that small firms do not have to build everything themselves. Outsourced accountants, virtual CFOs and specialized cash flow forecasting services for SMEs can provide structured routines, models and independent challenge to your plans. At the same time, choosing the best cash flow management software for small business in your niche can automate 80% of the manual work: bank reconciliation, recurring invoices, reminders and scenario simulations. The sweet spot is to combine tools and advisors so your decisions are grounded in timely data, not guesswork or fear.

—

Common misconceptions about cash flow in downturns

Misconception 1: “If I’m profitable, my cash will be fine”

Many owners assume that as long as their profit and loss statement is positive, they are safe. In reality, you can show a profit while running out of cash because profit ignores timing. You might be booking revenue that has not yet been collected, or capitalizing investments that consume cash immediately. During downturns, this gap widens: customers delay payments, while you still pay staff and suppliers on time. That is why how to improve cash flow during a recession is a different question from how to improve profitability; they overlap, but they are not identical.

Misconception 2: “Cutting costs aggressively solves everything”

Brutal cost cutting can feel like decisive leadership, yet advisors warn that it is often blunt and risky. If you slash marketing that generates quick sales, or lay off people essential for service delivery, your short‑term savings can destroy the very cash streams that keep you afloat. A smarter approach is to analyze which expenses generate near‑term cash inflow, which protect long‑term value, and which are nice‑to‑have noise. The goal is targeted trimming, not across‑the‑board austerity that leaves a hollow shell of a business unable to recover once the economy stabilizes.

Misconception 3: “Loans are the only way out”

When cash gets tight, it is tempting to see bank credit or investor money as the main answer. While external funding can be useful, experts note that borrowing simply shifts the problem into the future unless the business model itself becomes more cash‑efficient. Before chasing new money, it is usually more effective to refine pricing, renegotiate terms, clean up overdue invoices and simplify product lines. These moves may be less glamorous than securing a big loan, but they build resilience and reduce dependence on lenders who may tighten standards exactly when you need them the most.

—

Bringing it all together

Managing cash flow during downturns is not an obscure financial art; it is a set of habits that owners and managers can learn, refine and pass on to their teams. History shows that the companies that survive are not always the most innovative or the largest, but the ones that treat cash as a strategic resource, not just an accounting afterthought. By adopting clear principles, drawing on realistic examples, and listening to experienced advisors, you can turn a recession from an existential threat into a demanding but manageable test of discipline.