Why Investing 101 Actually Matters (Even If You “Hate Finance”)

If you earn money and plan to keep living on this planet, you’re already an investor—whether you admit it or not. Leaving everything in cash is a bet that inflation won’t quietly eat your savings; buying a house is a bet on property; joining a pension plan is investing by proxy. This guide breaks down stocks, bonds, and index funds in plain English, so you can stop guessing and start making deliberate choices. We’ll also look at how to start investing in stocks and index funds step by step, where beginners get burned, and a few non‑obvious shortcuts that can save you years of trial and error.

—

Step 1. Get Clear on What Investing Actually Is (and Isn’t)

Investing is simply exchanging money today for the possibility of having more money later, in exchange for taking some level of risk. It is not the same as trading, gambling, or “playing the market” on your phone every 15 minutes. Investing focuses on owning productive assets—companies, governments, real estate—that generate cash flows, dividends, interest, or growth over time. The analytical approach here is to ask one core question: “What real activity in the world ultimately produces the money I hope to receive from this asset?” If the honest answer is “someone else will buy it from me for more,” you’re closer to speculation than investing.

—

Step 2. Stocks in Plain English

What a Stock Actually Represents

A stock is a tiny slice of ownership in a company. If the business makes profits and grows, your slice tends to become more valuable over the long run. You may also receive dividends, which is just a portion of the company’s profits paid out to shareholders. When people think about a beginner investment portfolio with stocks and bonds, stocks are usually the “growth engine” because businesses can expand, raise prices, and innovate, while bonds are more about stability and income.

Why Stocks Feel Scary (But Don’t Have to Be)

Prices of stocks jump around daily because investors constantly update their expectations about future profits, interest rates, and risk. On a one‑day chart, the market looks like chaos; on a twenty‑year chart, broad stock markets in developed countries historically trend upward despite recessions, wars, and crises. The danger for new investors is emotional: you see a red number, feel pain, and want to “fix it” by selling. This is how people lock in losses. The smarter stance is to decide in advance how much volatility you can tolerate and then choose stock exposure that fits that tolerance, rather than trying to outsmart every price swing.

Non‑Standard Stock Idea: “Set a Panic Script”

Instead of promising yourself “I won’t panic,” actually write a one‑page “panic script” before you invest. It might say: “If my portfolio drops 30%, I will not sell. I expect this to happen at least once every 10–15 years. Instead, I will (a) re‑read this note, (b) look at a 30‑year market chart, (c) stop checking my account for 60 days.” Having this pre‑commitment document is like installing psychological seatbelts. It is a surprisingly powerful way to keep your future self from doing something destructive in a moment of fear.

—

Step 3. Bonds in Plain English

What a Bond Actually Is

A bond is an IOU. You lend money to a government or a company; in return, they promise to pay you interest regularly and return your principal at a fixed date. Government bonds from stable countries are usually considered safer but pay lower interest. Corporate bonds are riskier but may pay more. Unlike stocks, bonds have a maturity date—an endpoint when the principal comes back, assuming the borrower does not default. This built‑in endpoint can make bonds feel more predictable and is why they often appear in retirement portfolios.

How Bonds Behave (and When They Can Surprise You)

Bond prices move mainly because of changes in interest rates and perceptions of credit risk. When market interest rates rise, the prices of existing bonds generally fall, because new bonds are issued with better yields. Beginners often assume bonds only go “sideways and safe,” then get confused when their bond fund drops in value during a rate spike. This is not a failure of bonds; it is the expected mechanical relationship between prices and yields. Over longer horizons, interest income and reinvesting at higher rates can offset those price drops.

stocks vs bonds which is better for beginners?

Neither is “better” in the abstract. Stocks offer higher long‑term returns with more volatility; bonds offer more stability with lower expected returns. For someone with decades ahead and a stable income, a stock‑heavy portfolio might make sense. For someone close to retirement or with a fragile job situation, more bonds are often appropriate. A more analytical framing is: “How much can I afford to see my account drop in a bad year without losing sleep or abandoning the plan?” Stocks fill the part of the portfolio that seeks growth above inflation; bonds anchor the part that lets you emotionally stay invested.

—

Step 4. Index Funds: The Cheat Code Most Pros Use

What an Index Fund Does

An index fund is like a big shopping cart that holds tiny slices of many companies or many bonds, designed to mirror a market index (such as the S&P 500). Instead of paying highly for a manager to pick winners, an index fund simply owns everything in a category at very low cost. Over time, the average performance of the market, minus tiny fees, has historically beaten most actively managed funds. That is why many experts quietly build their personal wealth primarily with index funds, even if they talk about “stock picks” in public.

Why Index Funds Are Friendly to Beginners

You do not have to analyze balance sheets or guess which CEO will succeed. When you buy a broad stock index fund, you implicitly own thousands of businesses across many industries and countries. Individual disasters—fraud, bankruptcy, disruption—barely move your overall result because the failures are diluted by all the winners. For that reason, when people look for the best index funds for beginner investors, they often end up with broad, low‑fee funds that track large diversified markets rather than niche sectors or trendy themes.

Non‑Standard Index Idea: “The Anti‑Excitement Rule”

If a fund feels exciting, that might be a warning sign. Sector funds, leveraged funds, ultra‑narrow themes—these often sound intellectually thrilling and make great headlines, but they also concentrate risk. A practical rule: if you feel the urge to brag about a fund at a party, cap that holding at 5–10% of your portfolio and keep the rest in boring, diversified index funds. Let your excitement live in the small sandbox, while your long‑term wealth sits in broad, unglamorous indexes.

—

Step 5. Building a Beginner Portfolio with Logic, Not Guesswork

A Simple Allocation Framework

One common starting point is to decide how much of your portfolio goes into stocks versus bonds based on your time horizon and risk tolerance. A rough heuristic: the longer you can leave the money untouched, the higher the stock percentage you can usually tolerate. For example, someone in their 20s might choose 80% stocks and 20% bonds; someone in their 50s might go closer to 60% stocks and 40% bonds. This is not a formula carved in stone, but a base you can adjust. The aim is not perfection; it is a portfolio you can stick with during rough markets.

Example of a Beginner Investment Portfolio with Stocks and Bonds

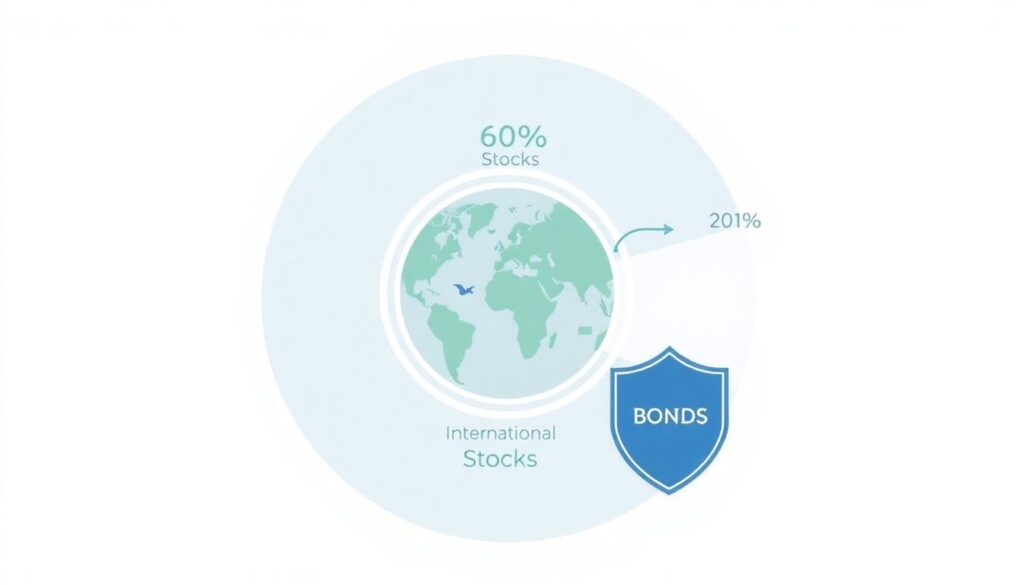

Instead of buying dozens of products, you could build a clean three‑fund setup: one broad domestic stock index fund, one broad international stock index fund, and one high‑quality bond index fund. For instance, 60% domestic stocks, 20% international stocks, 20% bonds. Each fund can be an index ETF or mutual fund, depending on what your broker offers. This type of portfolio is globally diversified, cheap to run, and extremely easy to manage. You can rebalance once or twice a year by shifting a bit from whatever grew more back into whatever lagged.

Non‑Standard Portfolio Idea: “Default Plus Play Money”

If you feel a strong itch to pick individual stocks or try strategies, quarantine that urge. Set a strict percentage—say 90% of your money in your boring, diversified core portfolio, and 10% in a separate “experiments” bucket. Track them separately. This approach satisfies curiosity and learning without hijacking your entire financial future. Over time, many people notice that their humble index core quietly outperforms their exciting experiments—a useful, humbling datapoint.

—

Step 6. How to Actually Start: From Zero to First Investment

Choosing an Account and Platform

Nowadays you can open an investing account in minutes. Many online investment platforms for index fund investing offer commission‑free trading, automatic investing options, and tax‑advantaged accounts such as IRAs or ISAs depending on your country. The analytical part is to decide: (1) Is this a tax‑advantaged retirement account or a regular brokerage account? (2) What are the fees—both explicit commissions and hidden fund expenses? (3) Does the platform let you automate contributions? Automation usually matters more than fancy features because consistent deposits beat sporadic bursts of enthusiasm.

Step‑by‑Step: how to start investing in stocks and index funds

1. Clarify your goal and time frame (for example, retirement in 30 years, or a home down payment in 7 years).

2. Decide your rough stock/bond split based on that time frame and how much volatility you believe you can handle.

3. Pick 1–3 low‑cost index funds that together match that split (for example, a global stock index fund plus a bond index fund).

4. Open an account on a reputable, low‑fee online platform and link your bank.

5. Set up an automatic monthly transfer into those funds, even if it is a small amount.

6. Create your written “panic script” and choose a check‑in schedule (quarterly or twice a year), not daily.

7. Commit to at least a five‑year horizon for stock investments so you are not forced to sell in a downturn.

This process may feel slow, but once it is configured, your system works in the background while you live your life. The hardest part is psychological, not technical.

—

Step 7. Classic Beginner Mistakes (and How to Dodge Them)

1. Chasing Hot Tips and Headlines

Buying what is currently trending on social media or in the news is a reliable way to buy high and sell low. By the time an asset hits front‑page excitement, a lot of optimism is already baked into the price. A calmer approach is to make decisions based on your written plan rather than current narratives. Before any trade, ask: “How does this fit my overall allocation, and what would make me sell it?” If you cannot answer in one or two sentences, you are probably acting on impulse.

2. Ignoring Fees and Taxes

A 1–2% annual fee sounds tiny, but over 30 years it can eat a shocking chunk of your eventual wealth because it compounds against you. That is one reason index funds, with their very low expense ratios, are so powerful. Likewise, short‑term trading can trigger higher tax rates in many countries. One unconventional but effective habit is to treat potential trades as if there is a “friction cost” every time you move: not just monetary (fees and taxes), but opportunity cost in terms of your time and attention. This mental accounting often nudges you toward fewer, higher‑quality decisions.

3. Overcomplicating the Portfolio

There is a strong temptation to add more and more funds to feel “sophisticated.” In practice, beyond a certain point, additional funds do not add much diversification; they merely replicate the market with more moving parts. A surprisingly large share of professional research suggests that a simple mix of a few broad index funds can match or beat far more intricate constructions. The unconventional move for a beginner is not to add complexity but to deliberately remove it until every holding has a clear, distinct role.

4. Investing Money You Cannot Afford to Tie Up

If you are likely to need the money within a year or two for rent, emergency expenses, or debt payments, putting it into risky assets is dangerous. A good rule is to separate your finances into layers: an emergency fund in very safe, liquid form; short‑term goals in conservative assets; and long‑term goals in stocks and bonds. This layered structure reduces the chance you will be forced to sell at the worst possible time, which is often when markets are down and you most need psychological stability.

—

Step 8. Non‑Standard Practices That Make You a Stronger Investor

Run “What If I’m Wrong?” Simulations

Instead of asking, “What if this investment works incredibly well?”, ask, “What if I am early, wrong, or unlucky?” Picture your portfolio down 40%. Would you still be able to pay your bills, sleep at night, and stay invested? If not, your risk level is too high. You can also simulate different economic scenarios—high inflation, job loss, medical emergencies—and see how your current plan holds up. This sort of mental stress testing makes your strategy robust rather than merely optimistic.

Design an Investing “User Manual” for Yourself

Create a short document that explains your goals, target allocation, rebalancing rules, and panic script. Include rules like “I will not check my account more than once per month” or “Before any new investment, I will wait 24 hours.” This manual turns vague intentions into explicit policies. Treat it like a small contract between your calm self and your future anxious self. When markets get noisy, you do not have to reinvent your philosophy from scratch; you simply follow your manual.

Measure Process, Not Just Performance

In the short term, returns are noisy and partially random. Instead of obsessing over whether you beat some benchmark each quarter, track whether you followed your process: Did you contribute the planned amount each month? Did you rebalance when your allocation drifted? Did you avoid impulsive moves during volatility? By evaluating yourself on behaviors you can control, you gradually build a stable investing identity rather than chasing luck.

—

Step 9. Putting It All Together

You do not need to become a market guru to invest well. You need a handful of clear ideas: stocks are ownership and growth; bonds are loans and stability; index funds are low‑cost diversification; and your personal behavior is the real leverage point. With that, you can use simple, diversified funds on mainstream platforms to build a resilient portfolio tailored to your life. Over time, small, consistent actions—automatic contributions, periodic check‑ins, and staying the course during storms—do most of the heavy lifting. The most unconventional thing you can do in a world obsessed with constant market noise is surprisingly simple: choose a sensible plan, automate it, and then have the discipline to leave it mostly alone.